Street Safety - The Basics

A couple of blogs ago we ended up with 4 key things to fix, and the first two we covered last time, as the "hard" people/culture sorts of problems. That leaves two "easy" technically-focused problems.

- Change street design to improve inherent safety and to promote better driver behavior.

- Shift our thinking from the 1950's car-first, zoning-heavy mobility strategy to a car-last accessibility strategy.

- Cars drive sprawl, which ends up being unsafe, uneconomic, and dehumanizing

- Applying roadway (actually, highway) design optimizations to streets turns them into "stroads", which are not safe or accessible streets for living/shopping/working, nor are they efficient roads for connectivity.

- Safe, human-scale, mixed-use neighborhoods are more pleasant, sustainable, financially viable, and useful than current suburbia

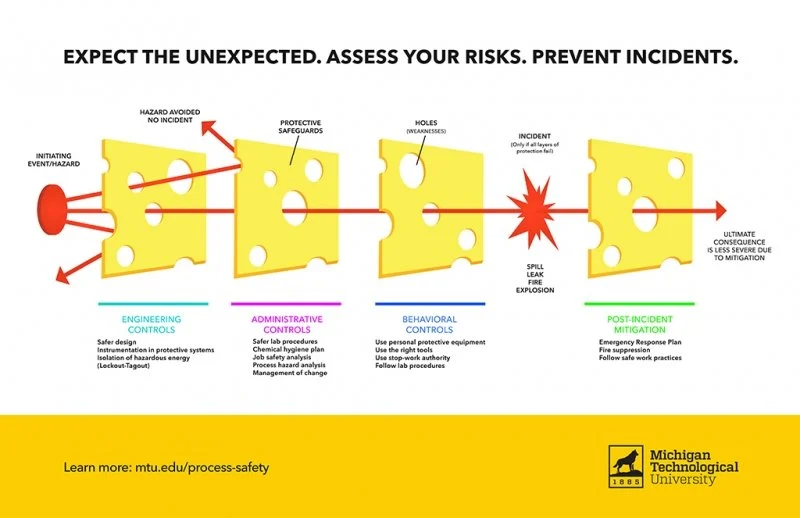

How do we make streets safe, recognizing as we've said before the systemic failures of humans which operate vehicles? We go make to our Swiss Cheese model, and think harder about "defense in depth", to address the fundamental failing of our current culture: individual responsibility. Car owners, when they purchase and operate a car, have a strong vested interest to keep the occupants of their car safe, but less so other road users, who must watch out for ourselves. For car-to-car interactions, we have two self-interested parties interacting with fairly symmetric vulnerability and hazard profiles with a design environment that has basic controls, so we have several slices of cheese:

- Engineered: my car's safety features, your car's safety features, the curbs, curves, sight-lines and other design features that govern vehicular operation,

- Administrative: lanes/signs/lights that guide our behaviors, and occasional police presence to reinforce proper behavior. We know that all of these slices of cheese have holes, and these holes line up pretty often. If an operator is tired, drunk, distracted, or otherwise impaired, there are still a couple of other slices to prevent "escapes", but still crashes happen routinely with various severity.

- Behavioral: your training and mine, cultural influences, legal and insurance ramifications, costs and incentives

- Mitigations: Deliberate features to make escapes less impactful

This vast asymmetricity of hazards is what the Dutch identified 50 years ago with the "stop the kindermoord" campaign, and look at our slices of Swiss we can see why they were right: if we take out one slice of cheese for the child, there isn't much left. The car-side slice protects that party completely against human crashes, yet a behavioral lapse by the driver leaves no protection for the human regardless of initiating event. It's a frail, single-point of failure system. Paint? Signs? Lights? Curbs?

These are all mild coordination mechanisms for observant drivers, and all can be readily overwhelmed by a vehicle. Thus we see "victim blaming" as a common outcome, as the driver attempts to place responsibility on the vulnerable human. In some cases, yes, that person did contribute, but we know we have a frail system with valid street users such as children who are not even legally responsible for their action.

To improve system robustness, we must add slices of cheese to our stack, using any/all of the disciplines in the diagram above. We have some decent options:

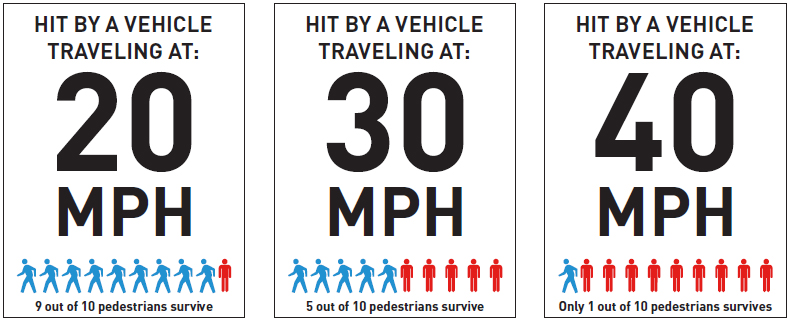

- Here's the easiest, as both a moderate behavioral control and a major mitigation option: where multiple user modes are present, and complete separation is not possible or currently in place, reduce speeds. 10mph should be a good maximum speed around children, and never more than 20mph around pedestrians of any sort (actual speed, not marked speed). This is simple, empirical physics at work. For our design culture, this is the new message: IT IS OK TO INTENTIONALLY SLOW VEHICLES TO REDUCE RISK TO OTHERS!

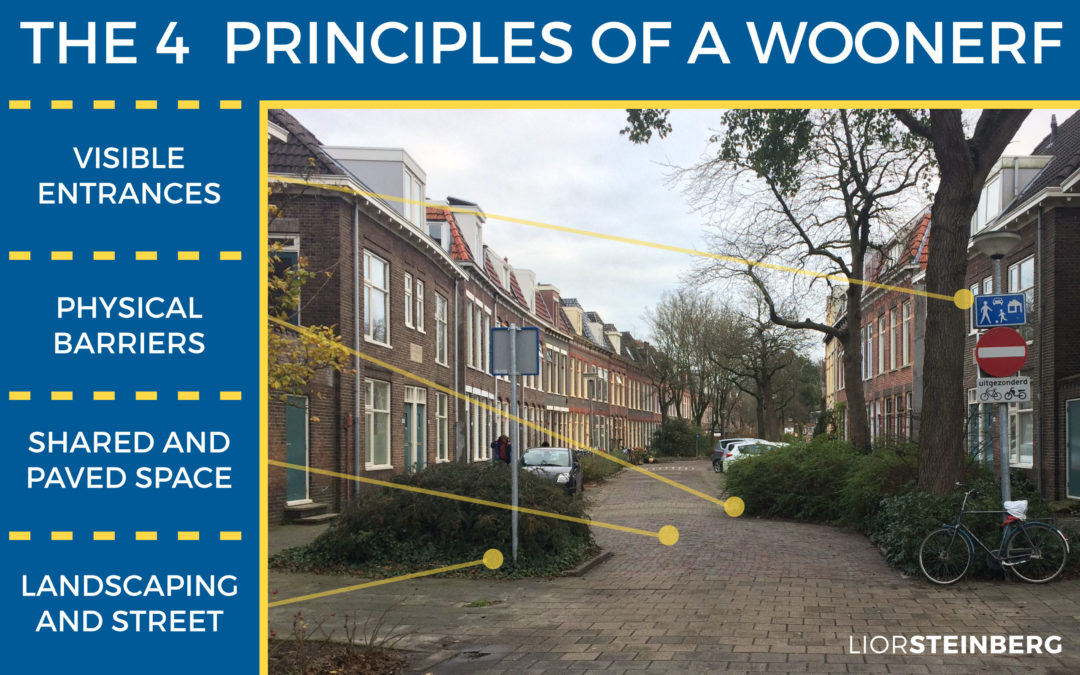

- As an administrative control, reduce or eliminate car usage in environments where human predominate, especially where there are children. This is the concept of a woonerf - few cars, no through traffic, very low speeds. Note that we should not have cars near schools, obviously (and yet this is our predominant model). IT IS OK TO INCONVENIENCE DRIVERS NEAR THEIR HOMES TO PROTECT CHILDREN.

- As an engineering control, provide firm modal separation, with concrete and steel, to ensure that cars stay where cars should be and other street users are safe from them. Today we tend to accommodate cars that err by providing break-away infrastructure, and instead we should willingly damage errant cars to protect other users. More bollards, fewer break-away poles. More trees and planters, less open space. We should do this even when cars are going slowly, and robustly when we want cars to exceed 20mph. IT IS BETTER TO CRASH CARS THAN TO CRUSH PEOPLE.

- As engineering and administrative controls, eliminate conflict points where drivers and other road users interact. This point reinforces the previous one. Let's say we have sidewalks nicely protected by trees and planters, and a separated bike lane with at least a concrete curb and some median, and a mix of ordinary car traffic heading toward local designations and maybe a bit of through traffic. WE SHOULD PRIORITIZE LOCAL RESIDENTS AND THEIR HUMAN TRAFFIC OVER THOSE PASSING THROUGH OR ATTEMPTING TO ARRIVE/DEPART.

- Along the road, we MUST eliminate curb-cuts aggressively, thereby preventing conflict points where drivers cross sidewalks and bike lanes. If a mid-block alley is needed for local parking, then have one such point. Cars don't park in the front of buildings, but either along the street or in dedicated parking off the alley. Note that curb-cuts basically create an uncontrolled intersection, with associated conflict points.

- Eliminate left-turns across traffic into any curb-cuts. This eliminate a gap-shooting risk where drivers are hurrying to avoid car traffic and miss cycles or pedestrians at the mid-block crossing conflicts. If you want left-turns into a mid-block point, add a light.

- Intersections represent multiple unavoidable conflict points unless underpass/overpass options are available. Simpler intersections are safer - look at all the conflicts even a basic intersection creates, and think about the holes that makes in our slice of cheese. Again, it's fine to inconvenience drivers to improve safety for non-drivers.

- No right-turn slip lanes. These create conflict when crossing cycle lanes and encourage high-speed turns. Use bulb-outs to make turns sharp and slow.

- No right on red. This is terribly obvious, and it's easy to do city-wide. Right on red means that drivers are focused on traffic coming from the left, looking for a gap into which they will aggressively jump. Yet a pedestrian properly coming from the left in front of them has right of way. The driver will tend to pull into the crossing, inconveniencing and threatening pedestrians. Worse, they may completely miss a pedestrian newly present from the right when he accelerates to turn.

- Add leading pedestrian intervals (LPI), scramble crossing phase, or other dedicated phases for pedestrians and cyclists. LPI is easiest, as it simply gives pedestrians a head start on crossing the street before car traffic begins moving, and helps eliminate the unavoidable right-turn conflict point if dedicated phases are not added.

- Eliminate mode overlap between signalized left-turns and a walk phase. Cars should not be provided signal approval to run over pedestrians.

- Where possible, simply eliminate signalized intersections. Go for slow, tight round-abouts or even 4-way stops.

- Another easy and obvious national improvement: ensure that on city streets drivers must stop for pedestrians desiring to cross at any valid crossing point. In many cities, pedestrians "own" the crossing once in the street, but the entry point is gray area where pedestrians are expected to wait for a gap (which may not occur). Simply require that being near the street indicates ownership, with pedestrians having priority over drivers.

- When in doubt, make decisions based on the order of vulnerability, with pedestrians then cyclists at the top, and individual drivers at the bottom of the order. Buses and transit go in the middle, if operating on the same streets. Commercial vehicles, like taxis and contractor trucks, go above private cars, but barely.

- A harder one: add automated pedestrian detection to vehicles, larger-vehicles first. It is OK to make it hard and expensive to drive in cities, and for vehicle owners to carry the cost of their hazard mitigation.

- Implement presumed-responsibility laws for crashes, where the vehicle operator is always at fault, in order of vulnerability, unless there is clear intent to the contrary.

- Along the road, we MUST eliminate curb-cuts aggressively, thereby preventing conflict points where drivers cross sidewalks and bike lanes. If a mid-block alley is needed for local parking, then have one such point. Cars don't park in the front of buildings, but either along the street or in dedicated parking off the alley. Note that curb-cuts basically create an uncontrolled intersection, with associated conflict points.

We'll come back to the last of our four problem points -- accessibility thinking -- in our next installment, but for now let's note how all these and other safety improvements will contribute to accessibility. With greater safety, we'll have more mode-share options. More safe options, and less convenient driving, will lead to fewer cars. This will enable a virtuous cycle of: safer streets -> modal diversity -> fewer cars -> less parking -> more amenities and fewer cars -> safer streets....lather, rinse, repeat.

Comments

Post a Comment