Street Safety - Better Boundaries and Swiss Cheese

Our last blog installment introduced the importance of system boundaries, and today we'll leverage that into new territory. If we can make it through the rest of the underpinnings in another posting or two, then perhaps after that we'll get into the meat of suggesting specific changes to our current way of thinking about and managing street safety.

Practically, it makes no sense to have Safety as a department that looks for issues but has limited influence - as noted previously, authority and responsibility must align. Many companies make this mistake, with the result that Safety looks bad due to injuries or death trends and turns into a career dead-end while Operations continues on its merry way chasing productivity gains.

In any large organization there must be a hierarchy, and typically over time silos develop with unique politics and ways of doing things, and over time these can may become insular with friction between silos. This cannot be much helped except by rebuilding the organization, so instead we must create the ability to cut across political domains inside the organization to align goals overall.

This means that for safety improvement to actually happen, we need at least two things to happen in our organizations:

- Safety has to be everybody's responsibility in a tangible way, which means "skin in the game". Having "skin in the game" means that it affects peoples paychecks and careers, and individuals feel a substantial desire to help achieve the corporate goals, and not passively look the other way or actively undermining the processes. Every business organization knows how to do this as all companies similarly accomplish such today for revenue growth by impacting raises, bonuses, and promotions.

- Safety goals and tracking must be visible and routine. Yes, these may be gamed for success theater, so it takes careful continuing attention, and this is where a specific safety department can help. It needs to cross-cut the rest of the organization in terms of authority, yet remain mostly responsible for the tools and processes. Each silo manager should be responsible for safety results in their domain.

- A Pig and a Chicken are walking down the road.

- The Chicken says: “Hey Pig, I was thinking we should open a restaurant!”

- Pig replies: “Hm, maybe, what would we call it?”

- The Chicken responds: “How about ‘ham-n-eggs’?”

- The Pig thinks for a moment and says: “No thanks. I’d be committed, but you’d only be involved.”

As part of aligning responsibilities, we need to draw system boundaries to match the real goals we want to see, and that implies not allowing political silos to draw these. This is a lot like not allowing politicians to draw their electoral maps, as politicians like to pick their voters even more than voters like to pick their politicians. For topics like safety, every silo owner would like to have safety metrics where they get an easy win, while the hard, unpredictable problems fall to somebody else (becoming SEPs). There must be "buck stops here" aggregate responsibility points such that the head of the organization has a strong interest to ensure that somebody lower in the organization has responsibility for these fixing hard problems.

Within the organization, there will naturally be strong interests in limiting liability for safety escapes, such that nobody is personally liable either legally or career-wise. On the one hand, this means that systems will be engineered to lean on standardized cookie-cutter guidebooks and processes with legal top-cover. This helps makes the systems more consistent and efficient, but it can also water down the effectiveness of accountability. Just as importantly, these guidebooks become part of the bureaucracy and its culture, making things harder to change when needed.

As Marohn points out in his excellent book "Confessions of a Recovering Engineer", automotive safety has improved drastically since the 1930's, and yet we still have 35-50K die, conservatively, every year. Clearly we know how to improve, and equally clearly we've got a lot to do.

Some nomenclature: A system that can tolerate multiple failures and gracefully recover or degrade safely is a "robust" or "resilient" system. Simplistically, we must deliberately eliminate single-points of failure and reduce the likelihood of failures in critical parts of the system.

It's not elegant, but simple trial and error based upon careful analysis of every "escape" and taking action to improve robustness will over time be effective. This "root cause(s) analysis" is why planes almost never crash, and why bombers make it back full of holes and with one engine gone. Such analysis requires discipline and deliberate investment as it requires learning hard lessons over time, and spending time learning from peers in similar situation; hopes and prayers a la VisionZero support statements will result in nothing without a budget and influence to make necessary changes.

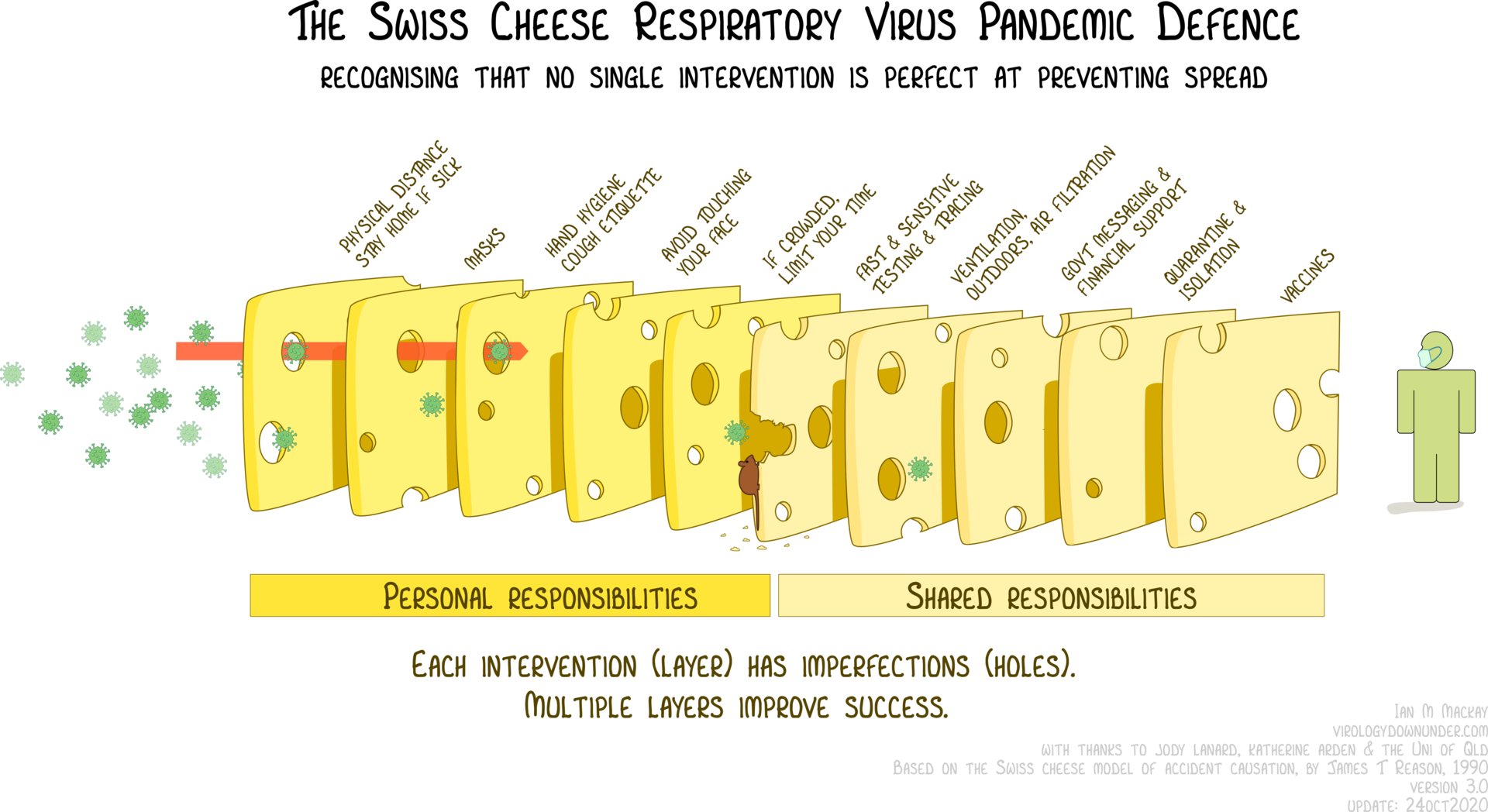

A good mental model to keep in mind, and one of my personal favorites, is the Swiss Cheese model, where every element of process protection against a fault is a layer of cheese.

- Since it's Swiss cheese, its got holes, which is to say that no process or protection will ever be perfect, and some failures will make it through a hole. The fewer and smaller the holes, the better the protection.

- Integrate a set of overlapping protections in your process, and now you have a stack of random Swiss cheese slices, and the resulting system is more robust. To have an escape, holes in all the slices have to line up for a fault to manifest.

- To improve robustness over time, the approach is straightforward: add more slices, or make the holes in existing slices smaller. This is what root-causes-analysis and corrective actions accomplish, over time.

- Here is a familiar example from our favorite pandemic, with COVID infection as an escape:

Getting back to the street safety pyramid we built a few days ago, every crash at the top of the pyramid is an "escape", as an alignment of holes in the cheese stack. Every injury is a fatality that didn't quite happen, occurring as a lower-cost escape, and every property loss incident is lower cost still. Every "near miss" is an obvious case where many holes aligned, yet one final slice managed to block the event or simple random luck saved the day. Hazard conditions are observed unnecessarily large holes in a slice of cheese.

- We lose a lot of available opportunity if we only investigate the worst escapes (or fail to investigate at all). We should not pat ourselves on the back for fortuitous outcomes, but cheer the opportunity to learn and improve from a relatively painless incident.

- If we "blame the victim", we put all our expectation of responsibility into a piece of cheese owned by the victim, and neglect to pursue other slices for which we are responsible.

- If we analyze and understand, but fail to make changes due to budget limitations or calcified culture, we remain in the realm of statistical inevitability, merely hoping that holes don't align again.

A trip not taken will have some loss of benefit to the individual and perhaps to the city and society overall, and this is the opportunity cost incurred for not investing in better layers of cheese. Given more transit options, accessibility improves, which means more alternative stacks of cheese for risks can be envisioned, and that a greater number of potential trips can make it past the cost-benefit analysis decision.

Let's pause here and repeat that concept: A trip not taken is generally a loss of benefit to the individual and their city. This is pretty important, because the "induced demand" that Brent Toderian and others talk about with lane widening, and the increased revenue for shops on more accessible multi-modeal streets, and the growth of economic complexity of a city overall compared to rural surroundings, are all related to this simple concept. If destinations are "accessible", this means the trip costs are low, and individuals can do more of them, and this turns into added value for all involved.

A few corollaries:

- In a city dominated by roads/stroads/cars, adding lanes will manifest "induced demand" because the only limiting factor (added trip cost) is time/frustration/risk spent in traffic congestion.

- In a city with multi-modal transit, Downs-Thompson paradox will tend to rule, where car traffic congestion grows until it's as slow as public transit. This is a natural outcome from trip-cost trade-offs, and is why good transit areas will tend to have better car driving experience as well.

- The better the accessibility, the stronger the inter-personal networks, and the higher the economic benefit to the individual and the city. People have more options for work and play, companies have better access to more workers, and serendipitous knowledge networks grow stronger.

Next post we'll dive into accessibility and safety from a cities perspective, and see if we can figure out why we've become car-only and why multi-modal safety has been such an intractable problem to solve.

Comments

Post a Comment