Street Safety - Everything We Did Was Wrong

Last blog we established a couple of pretty obvious changes to improve safety, but ended up asking WHY are our cities and streets (stroads) built this way? Here I have a bit of a confession: I've finished reading Marohn's "Confessions of a Recovering Engineer" and while I thought it would be mostly civil engineering, Marohn actually covers some of the system-level issues I'd been working on. He's done so more thoroughly than I probably could, so I'm not going to pick at those details. Cliffs notes:

- We purposefully decided to go all-in on car-centric mobility, and with an over-zealous and racially-tinged view of building suburban enclaves, we separated residential from commercial from industrial land uses, and we knit them together with roads.

- At the outset, many engineers didn't realize where this would lead, as the early model suburbs were "not that bad" in that they had slow, narrow residential streets to fairly slow collectors to faster arterials and fast highways. But the heavy spending on highways created most of the design standards, and these unfortunately trickled down into cities, creating the "stroads" we deal with now, and driving out all other modes of transportation by creating unsafe, uncomfortable, and not very useful environments for any other mode.

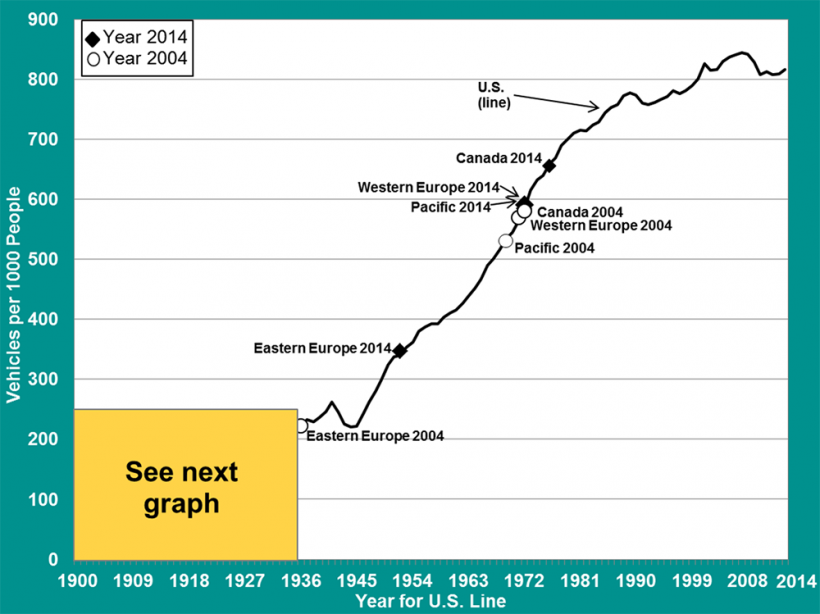

I'll expand on this a bit and note that engineering had a lot of respect in the 50's and 60's, and not without reason, but the overly narrow focus on mobility created a lot of knock-on effects that grew over time, especially due to parking (remember there are about 9 parking spots for each car, so your cars likely dominate more space than you do, not even counting road space) and local traffic.

To knit together far-flung jobs, shopping, and residential areas, not only did we push for faster roads, but we prioritized through traffic over local residents. The view, even until today, is to get cars where they need to go quickly.

Over time, as we noted a few blogs back, governmental power structures tend to calcify, becoming legalistic and bureaucratic. Street design is now much that way, with far too much entrenched policy that prioritizes cars and highway-centric design approaches. Real "engineering" to solve specific problems is too often turned into rote application of poorly matched handbook guidelines. Legal ramifications reinforce this, both in terms of individual responsibility for drivers, pedestrians/cyclist, and for street designers.

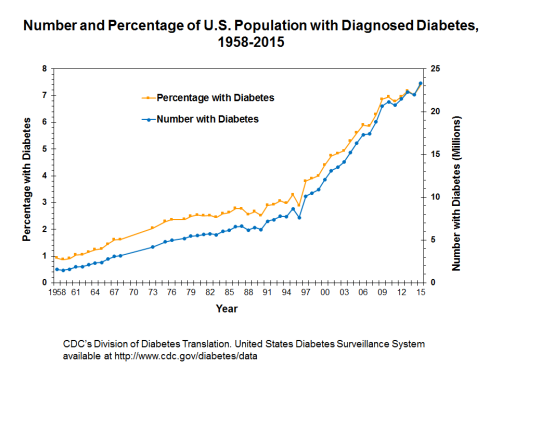

In the 50's, as engineers were focused on solving a few obvious problems, the notion that obesity and sedentary, isolated lifestyles based on too much time in cars, too little time walking, and far fewer moving jobs and far more sitting ones, would drive the bulk of our mortality rates was not at all obvious. But it is now. Take a look at the top-10 mortality list, and consider how driving, crashes, and lack of exercise contribute:

Perhaps I over-generalize, but now I often say "everything we've done since the 50's is wrong". Of course that's not literally true, but for city design it mostly is. We led the world in creating a high-mobility, individual-responsibility society, and certainly some of the reasoning was sound, but we've failed to revisit our priorities as emergent behaviors manifested in our complex system, and now we're paying the price. Our problems today are very much tied to our deliberate solutions from yester-year.

So, in my view we have four major problems to solve:

To knit together far-flung jobs, shopping, and residential areas, not only did we push for faster roads, but we prioritized through traffic over local residents. The view, even until today, is to get cars where they need to go quickly.

Over time, as we noted a few blogs back, governmental power structures tend to calcify, becoming legalistic and bureaucratic. Street design is now much that way, with far too much entrenched policy that prioritizes cars and highway-centric design approaches. Real "engineering" to solve specific problems is too often turned into rote application of poorly matched handbook guidelines. Legal ramifications reinforce this, both in terms of individual responsibility for drivers, pedestrians/cyclist, and for street designers.

In the 50's, as engineers were focused on solving a few obvious problems, the notion that obesity and sedentary, isolated lifestyles based on too much time in cars, too little time walking, and far fewer moving jobs and far more sitting ones, would drive the bulk of our mortality rates was not at all obvious. But it is now. Take a look at the top-10 mortality list, and consider how driving, crashes, and lack of exercise contribute:

- Heart disease: 659,041

- Cancer: 599,601

- Accidents (unintentional injuries): 173,040

- Chronic lower respiratory diseases: 156,979

- Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases): 150,005

- Alzheimer’s disease: 121,499

- Diabetes: 87,647

- Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis: 51,565

- Influenza and pneumonia: 49,783

- Intentional self-harm (suicide): 47,511

Perhaps I over-generalize, but now I often say "everything we've done since the 50's is wrong". Of course that's not literally true, but for city design it mostly is. We led the world in creating a high-mobility, individual-responsibility society, and certainly some of the reasoning was sound, but we've failed to revisit our priorities as emergent behaviors manifested in our complex system, and now we're paying the price. Our problems today are very much tied to our deliberate solutions from yester-year.

So, in my view we have four major problems to solve:

- Figure out how to make somebody in relevant authority responsible AND accountable for street safety

- Alter our social and legal responsibility for crashes from individual obligation to collective responsibility.

- Change street design to improve inherent safety and to promote better driver behavior.

- Shift our thinking from the 1950's car-first, zoning-heavy mobility strategy to a car-last accessibility strategy.

Comments

Post a Comment