Street Safety - System Boundaries (and SEPs)

"An SEP is something we can't see, or don't see, or our brain doesn't let us see, because we think that it's somebody else's problem. That's what SEP means. Somebody Else's Problem. The brain just edits it out, it's like a blind spot." - Douglas Adams, Hitchhiker's Guide the Galaxy

Today will be a bit of Systems Engineering 101 as we spiral into designing deliberately for Safe Accessibility. Full disclosure: I'm a Systems Engineer, by education and experience. I'm one of those big picture guys annoyingly asking "why?" a lot, and often pointing out the obvious. I'm not the 6-decimals of precision sort of engineer, but the 10% is good enough, add safety factors, measure by micrometer, mark with chalk, cut with an axe sort. I love feedback loops and low-gain systems that provide a nice stable base to work with.

This applies here because I'm not just a SE at work -- I'm that way all the time, about all sorts of things. Ever see a Border Collie trying to herd ducks, because, well, that's what he does? That's me. Just ask my wife.

First, let's define a system, just for fun (fun for me, at least): A system is a combination of related elements working together to achieve a common function. Almost anything can be a system, and you can have systems of systems in various hierarchies, and of almost unlimited variety. Humans are systems, and so are cars and bicycles, as are cities and nations, and the internet and highway network.

A frequent question I hear is "OK, I kinda see that, but how do you draw the boundary? And why do YOU get to pick?". The answer is "wherever I want" and "because I'm the systems engineer." That's a bit flippant, because lots of people draw boundaries for various purposes, and it is in the boundary that there is hazard. Let's talk about why.

Let's say you're a mechanical or civil engineer building a simple steel bridge. It's relatively easy to draw a boundary around the bridge and draw free-body diagrams and forces for it. You can also draw a boundary around a particular joint to analyze that. You draw the lines where it makes sense to make the math tractable and since it's a static (hopefully) construct all the pieces add up and fit together nicely. It works really well, and by now we're REALLY good at designing bridges.

However, complex systems are rather different.

- Complex systems have interacting components that are impossible to predict very far into the future with great precisions -- they are to some degree time-dependent

- Complex systems are more than just complicated (lots of parts), in that have sophisticated and often impossible to precisely understand interactions between parts.

- Most complex systems exhibit "emergent behaviors", which is a fancy way of saying "unexpected side-effects". It turns out that often such manifested behaviors are bad, so you should always worry when a SE looks into your system and says "that's interesting."

- It's hard to see inside the works of a complex system, and so it's hard to know what to change to get a desired shift in system behavior. It's easier if you can add feedback loops. "What the world needs is fewer clever designs and more basic feedback loops" - somebody wise. But in any case we have solutions for this:

- We say "Today's problems are generally caused by yesterday's solutions". This is also called "job security".

- We use a sophisticated closed-loop iterative optimization process. I call this "trial and error."

- We work closely with software people to build models so when a behavior manifests, we can say "it's a feature, not a bug" with a high degree of sincerity.

The great thing about complex systems in an environment of other complex system is that they interact, and so their mutual behavior changes over time. This means there is never a perfect long-term system solution; if it works now, and you leave it alone (and probably you should, but that's a redneck law, not a systems engineering one), it'll eventually break in some way all by itself. This is again called by systems engineers "job security."

- Truism #1: there are no hard technical problems; hard problems are people problems.

- Truism #2: everything that involves people is a complex system.

- Truism #3: all complex systems will eventually evolve to exhibit undesirable behaviors all by themselves.

- Unfortunate Corollary: all systems involving people wil tend to eventually exhibit unacceptable behaviors that will involve resolving hard problems

So, now that we've laid a nice firm basis of mud on top of used couch-cushion foam, let's dive into the crux of the system boundary issue:

- If you draw a boundary, you're interested in what happens inside the system (the behaviors), and what crosses the boundary going in and out (the inputs and outputs). Everything that happens outside the system is not of much interest, and these things have a name: Externalities. We don't worry about externalities because, well, they are external, and therefore a SEP -- see the quote at the start of this post.

- This is a very powerful tool, as it enables you to focus on what IS of interest, and learn and understand a lot, and to better model it and maybe even solve the problems at hand.

- This is also a significant risk, because not only are externalities not accounted for in your system analysis, meaning that costs, impacts, pollution, hazards, resource exhaustion, and everything else outside are not your concern and may be invisible, but they may (1) not be accounted for by anybody else's "system" either, and (2) may come back to bite you hard, as part of some broader system that includes both you and the selfish little system you just optimized.

- This is why I say "for Americans, globalism means never having to say you're sorry"

- This is why Libertarians really like the system boundary that they draw around themselves individually and their personal interests

- This is one reason why CEOs and politicians really like corporate capitalism with clear gov't regulation. And why they tend to be sociopathic, but that's another topic.

- If you draw a boundary around cars, it's easy to make cars safe, comfortable, and useful for occupants without worrying a whit about impacts the world at large.

- If you draw a larger boundary and take an analysis snapshot of cars on a street with other humans, you may get somewhat a different view.

- If you draw a boundary around your suburb, and then city, and consider decades of evolution, you will surely find many previously ignored impacts.

- If you make it the entire earth, there are more impacts still.

- In the first case -- looking only at cars, you ignore pollution, noise, hazard, and all other impacts to other people in the surrounding environment -- you're living in an automobile advertisement. In the second, you worry about local-level pollution, hazards, and noise, and suppression of active transit modes -- and perhaps you note some emergent behaviors. At the suburb level 20 years on, you now have manifested behaviors like sprawl, kids being driven to school in buses and cars, isolated seniors, house-bound people with disabilities, and anti-social neighbors (many becoming libertarian -- see above). Oh, and a generation of chubby couch-potatoes who rarely get exercise outside of deliberate car trips to a gym.

- At the global scale, you may have child-labor assembling car parts in far-off countries, global climate change, off-shored industrial waste, and the role of global corporations and lobbyists in local politics.

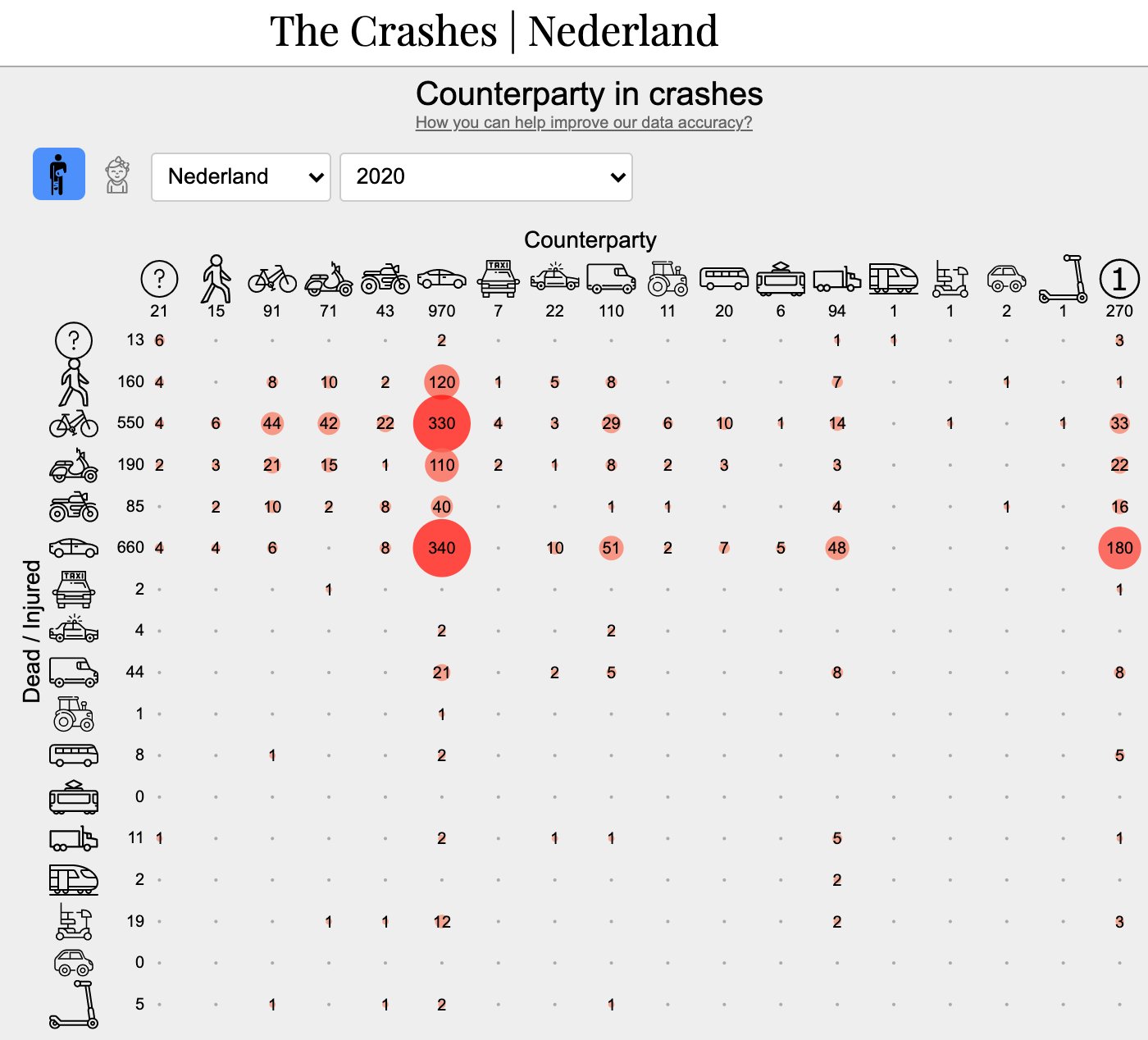

So, let's look at safety. In the US, first-order vehicle-related deaths are 40-50K per year. This is a lot, as a top-10 killer, and the most serious killer overall in some age groups. It's instructive to see that such deaths are not random related to trip modality (see the table below -- yeah, it's not for the US, but hey, I'm lazy and my system boundary today is apparently Dutch-aligned), but are tightly clustered by modal interactions. If we put our SE hats on, we can already see there are areas to look at more closely, and we can anticipate that hidden somewhere inside will be some "easy" technical problems and some "hard" people problems.

Before we dig in, let's think about deaths related to cars NOT captured by the analysis of this "system".

- Of suicides, what fraction should be allocated to increased social isolation due to cars? Suicide is a top-10 killers.

- Of pollution deaths, what fraction should we de-externalize? If vehicles use 30% of US energy, and the US uses 20% of world energy, then can we fairly include 6% of global pollution deaths on top of the previous tally?

- Of deaths due to climate -- flooding, hurricanes, heat waves -- can we do a similar accounting?

- Ah, but here's the kicker: obesity. The growth of obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and other "sedentary lifestyle' diseases is heavily correlated to our shift to driving more and walking less. These deaths represent maybe half of the top-10 killers. How many of these deaths can we pile on cars? All of them? Half?

- And yet there are more. That crime wave of the 80's-90's -- how much was due to lead poisoning from auto-exhaust for inner-city kids (or lead paint, or lead water lines like in Flint)?

- Anyway, with our "highway safety" focus, the gov't boards for NTSP, NHTSA, and NACTO do not worry a bit about these, as they are clearly externalities for their system -- they are SEPs. Car manufacturers are happy with this. So are gov't bureaucrats. And city planners. And, honestly, so are most of us. Who IS the voice of these externalized dead? Who is responsible and accountable for them?

Comments

Post a Comment